A Tale of Two Parks

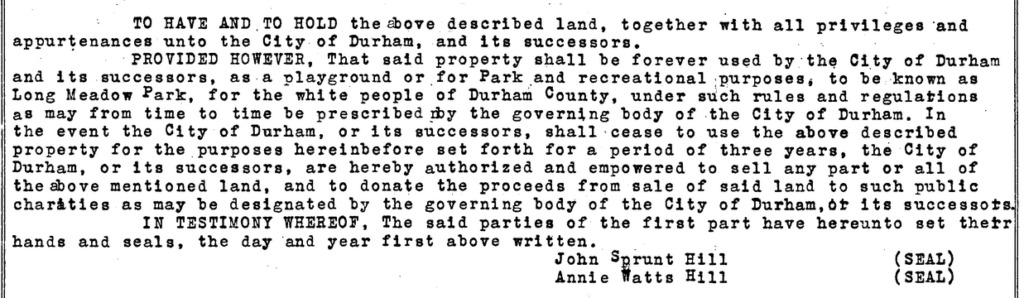

In Durham, there are two parks situated within a ten-minute walk from one another that were established at around the same time in the 1930s: East End Park and Long Meadow Park. Both of these parks were constructed on property donated by John Sprunt Hill but had distinct communities that they served: Long Meadow park, as stated in its recently transcribed property deed, served Durham’s white community, and East End Park served Durham’s Black community.

Despite being roughly a block apart from one another, Long Meadow Park and East End Park were considered to be a part of two separate neighborhoods in Durham according to Open Durham, the former belonging to East Durham/Edgemont and the latter belonging to East End, one of Durham’s historically Black communities. The closeness of these neighborhoods did not lead to equal renovations for these parks until desegregation. As we can see in the old aerial photos shared on Open Durham, Long Meadow benefited from a relative scenic attractiveness that East End Park didn’t have because of its location near industrial sites.

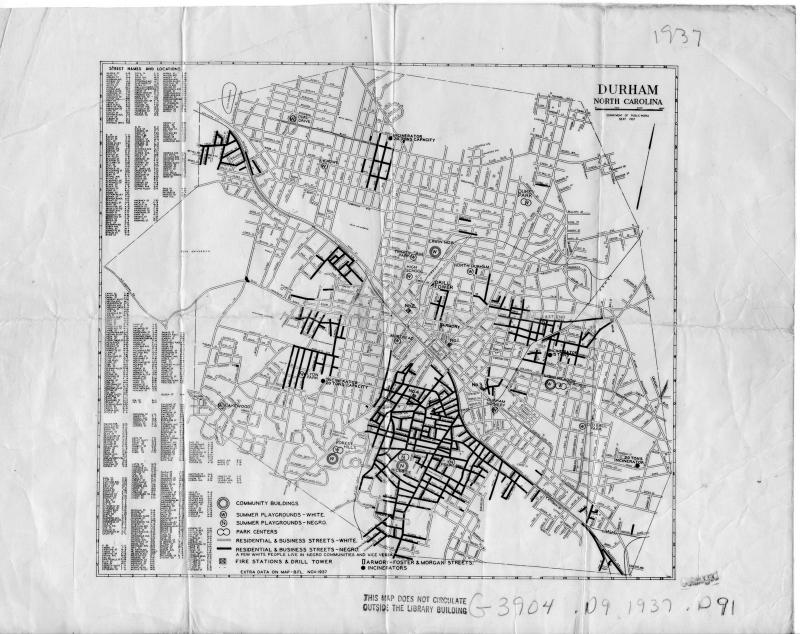

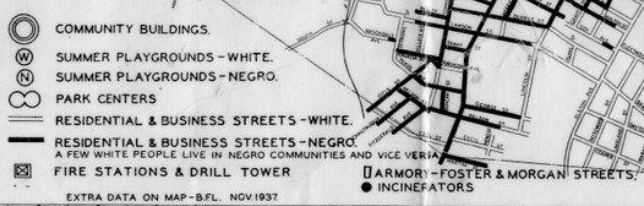

This inequality was not uncommon for parks situated in or near predominantly Black neighborhoods in Durham during the Jim Crow era. According to Cooper, Liberti, and Asch’s 2016 survey on replanting trees around Durham, three out of the eight parks that were established for Durham’s Black community were built near abandoned incinerators. Here is the map they reference from the Bureau of Public Works:

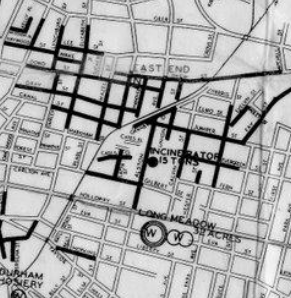

If we look closely at the area where East End and Long Meadow were established, we can see a deliberately segregated and unequal plan for these two parks:

When I zoomed in on this area, I was at first surprised to find that Long Meadow Park is represented while East End Park isn’t. I knew the location of the incinerator north of Holloway Street was exactly where East End Park was supposed to be, and the map’s legend clearly illustrates Long Meadow Park’s establishment as a white park center and the East End neighborhood’s predominantly black residence right across the street. Additionally, Open Durham shares that East End Park was built in 1932, and this map is dated November 1937. However, Open Durham also says that East End Park was modified in 1949, which I was able to corroborate with this issue of the Carolina Times (Durham’s main Black newspaper in the 20th century) that details how it was finally dedicated in 1950 after roughly three years of building picnic areas and such. I didn’t expect to run into these timeline issues, but they were still educational: if East End Park was not officially established until circa 1950, then that means the East End community didn’t have equal access to a park of their own while the predominantly white East Durham/Edgemont community did for roughly two decades prior.

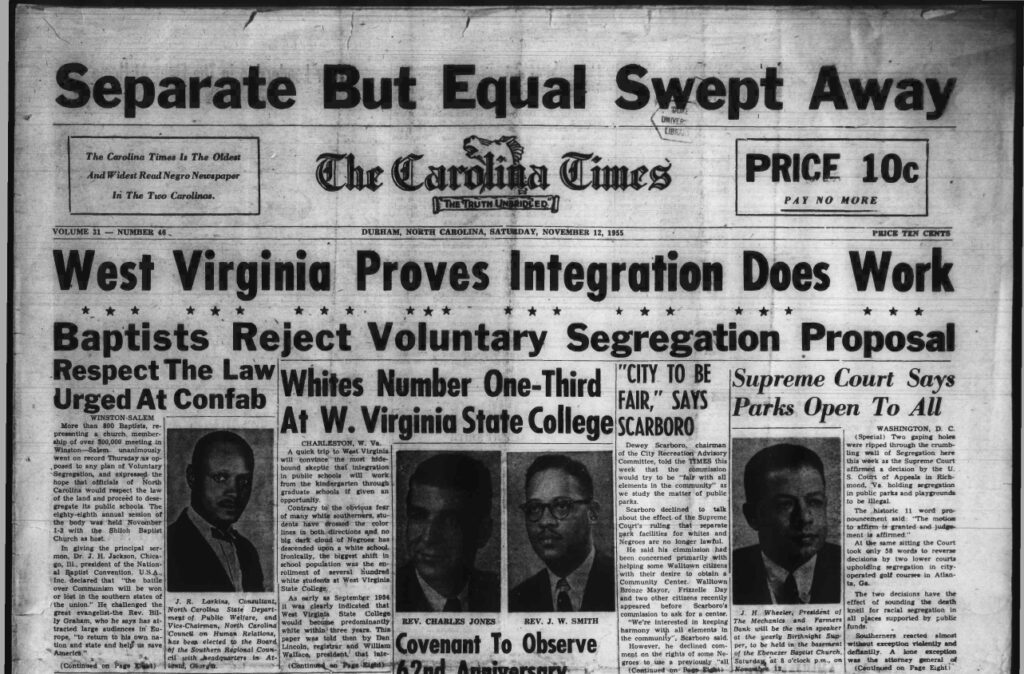

Deciding to pursue this timeline issue further, I searched through several more Carolina Times issues in the Digital NC database to see if I could find when these parks were desegregated. I found the 1955 issue above that reports that the Supreme Court ruled the segregation of parks and playgrounds unconstitutional in the United States. However, they also report that North Carolina, like many other Southern states, responded with agitation and sluggishness.

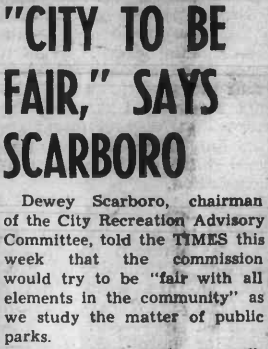

This issue details that then-chairman of the City Recreation Advisory Committee Dewey Scarboro held that this ruling “would not be immediately applicable to the Durham area” and that his main concern in this effort was with “keeping harmony with all elements in the community.” Put simply, his perception of fairness was with continued segregation in Durham. If we read further to where this article continues on page eight, we can see that this position ignored the reality of integrated play already taking place at Long Meadow regardless of its establishment as a white-only park.

When looking through the deeds database for Durham County, we noted that several parks had racial covenant clauses on the deeds.

This racial covenant clause in the property deed of Long Meadow Park gives us a glimpse into how the establishment of these two parks in Durham reflected a larger trend of segregated parks on both the local and state level in North Carolina. According to Cooper, Liberti, and Asch, the eight parks established for Durham’s Black community totaled 33 acres in comparison to the 174 acres of Durham’s 15 white parks, and, by at least 1954, all state parks in North Carolina but Reedy Creek and Jones Lake admitted only white visitors.

North Carolina attracted more than just white visitors, however. While exploring the North Carolina Museum of History’s parks exhibit, I found that NC experienced a boom in tourism during its Variety Vacationland campaign of the 1930s-1970s that promoted its state parks and historic sites to tourists. Despite the vast majority of these recreational areas only being open to white visitors, these tourists included people of color as well. Searching through the State Archives Digital Collections, I found the letters below that show that Black tourists seeking the same promises of leisure, adventure, and discovery in North Carolina were considered a “question” that the Department of Conservation and Development needed to answer.

I also found the photo below in the State Archives Digital Collections, which appears to indicate that the Division of Parks and Recreation initially assumed Black visitors to state parks in North Carolina were incapable of keeping park facilities clean and intact.

As the note in the above photo states, the North Carolina Parks Division planned to establish a second state park for Black visitors after the success of Jones Lake since its opening in 1939. It took until 1950 for the next black-only state park to open, Reedy Creek, which was an offshoot of the Crabtree Creek State Park that used to have separate entrances for Black and white visitors. We can see that the trend of unequal distribution of parks land between Black and white communities in Durham continues with the case of Reedy Creek and Crabtree Creek. According to the NCPedia, Reedy Creek visitors had access to 1,234 acres of land that used to be a part of the 5,000-acre span of Crabtree Creek. After Reedy Creek opened, Crabtree Creek closed its black-only entrance and became a white-only park.

It took until the 1966 integration of Reedy Creek and Crabtree Creek under the new name of William B. Umstead State Park for park visitors, Black and white alike, to have access to the same acreage. Now, many decades later, Long Meadow and East End Park can similarly be seen as an integrated pair. They have enjoyed valuable renovations like the Little League baseball diamonds that the Durham Bulls donated to Long Meadow Park in the 2000s. But what we see today when we visit these parks or pass by them on the road is, of course, not the full story. When we unearth primary sources like the property deed of Long Meadow Park, we ensure that the improvements we see today in Durham’s parks do not represent the whole history of their development. Instead, we can see how these parks reflect a larger trend of unequal and inequitable parks establishments in North Carolina on a state level. By helping transcribe the racial covenant clauses on these property deeds, we can make these complex, intertwined histories more accessible. We invite you to share your stories about growing up playing in Durham’s parks in the comments and hope that you will join us on Zooniverse to continue the important work of transcribing Durham’s property deeds.

Carrie Wilson is a Master of Library Science student at North Carolina Central University who will be graduating in May 2022. They served as a graduate research assistant for the Hacking into History team during the fall semester of 2021. Their main passions in the fields of librarianship and archives are digital inclusion and resource accessibility.