The Franchise Model of Inequity

The Hacking Into History project

Hacking Into History: Reckoning With Racial Covenants in Durham County is a collaborative project between DataWorks NC, The School of Library and Information Sciences Library at North Carolina Central University (NCCU) and the Durham County Register of Deeds. Using community-generated data, the project team and participants unearth racially-restrictive covenants in Durham property deeds between 1920 and 1970. By engaging with the covenants within an anti-racist space of shared story and mutual practice, we defy these monuments to hate and use them as guideposts toward transformative justice.

We’ve experienced racism; the building of white privilege throughout the nation as a franchise model. We have, as a nation, managed to have it codified in many ways, and then repackaged so that people can take that model and place it in their community and replicate it over and over and over again.

Tia Hall, Yinsome Group LLC

The franchise model

Many of Durham’s property deeds read like a business franchise agreement; an operating model often formatted as a formulaic listing of what is considered acceptable and unacceptable. There are a few benefits to this model:

- It’s “tried and true.” Buyers don’t need to start from scratch and therefore risk legal or operational challenges.

- It offers a brand image that can be easily replicated.

- The franchise model is an established agreement, which normalizes and legitimizes the practice.

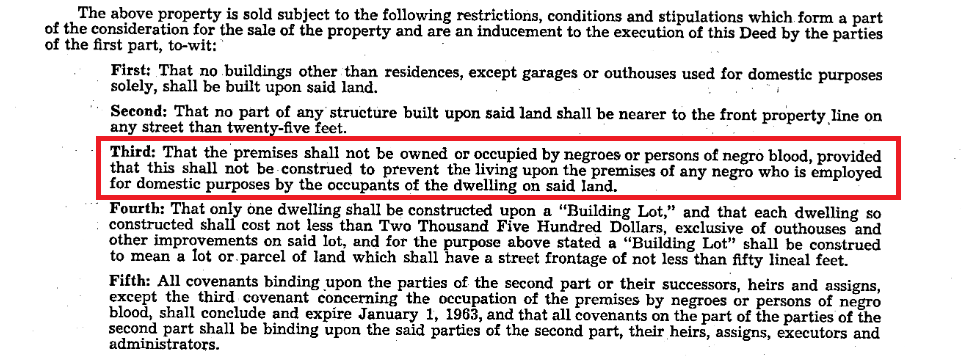

With property deeds, residents who signed these contracts were not only saying ‘yes’ to restrictions on dwelling costs or building sizes, but who was welcome in their neighborhoods, and who was not. The language is jarring.

Like holding any heavy truth, interacting with racially-restrictive covenants is painful. During the facilitated transcription meetups, Tia Hall often asks us to be aware of where that pain or discomfort manifests in our bodies as we confront uncomfortable information. Because it is uncomfortable, a common response is a desire to ignore it. Another is a desire to take immediate action by erasing these covenants from the deeds. However, removing the language from property deeds will not undo the harm it caused, and it does nothing to confront the racist and restrictive practices that live on under different names in Durham housing. We have to remember and hold these acts of violence if we want to avoid repeating history and truly move toward an equitable Durham.

Redlining and research on structural racism

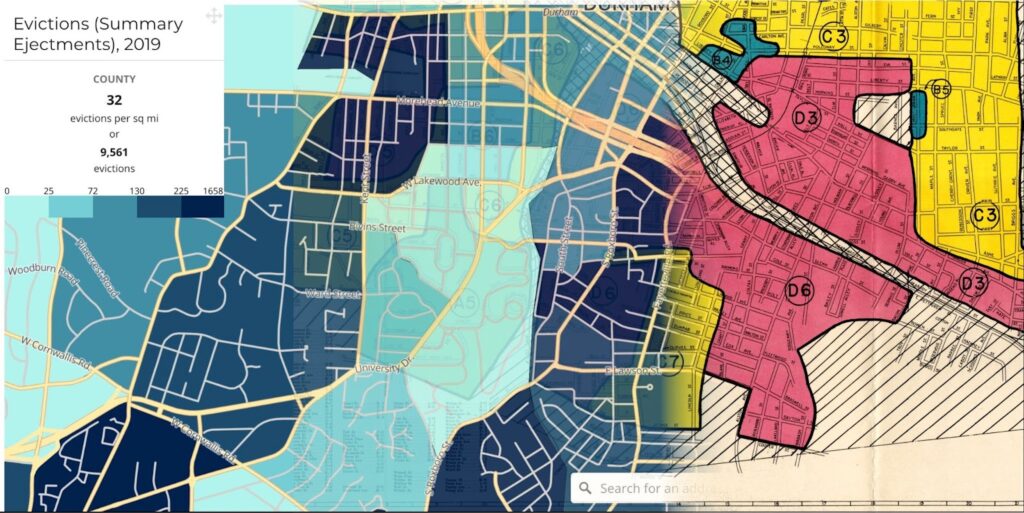

The franchise model also opens the door for opportunistic research and allows well-intended research efforts to oversimplify structural racism. As public dialogue becomes more aware of structural racism, racist practices in housing have come to the forefront of the conversation. Redlining has become a popular symbol of structural racism, perhaps because it is so obvious and easily quantified.

There’s a growing body of new health research assessing impacts of redlining, but the singular focus on redlining is reductive and potentially harmful. It’s great that public health is directly examining structural racism more often, but we want researchers to be more thoughtful as we do it. We recommend this blog post by Alex Hill: https://metropolitics.org/Before-Redlining-and-Beyond.html.

In it he says that it is not the “HOLC maps that are important, but instead what these maps and other practices tell us about the ways in which racism is deployed through the mundane use of data…and the scaffolding of policy and institutional practice that support segregation.” And further, that “the greatest disservice in fetishizing redlining is done to those most affected by historical and current spatial racism.”

Racism in housing did not begin with HOLC’s maps or the FHA’s lending practices in the 1930s. The land we now call Durham was settled by whites and stolen from Shakori, Occaneechi, Cheraw, Skaruhreh, and Lumbee people. Housing in colonized Durham was built for workers, established with racial restrictions, and many of the racial restrictive covenants included in our transcription work are from much earlier than 1930.

Furthermore, structural racism in housing did not end with the Fair Housing Act of 1968. The same inequities continue in Durham, under differently “branded” practices–gentrification, displacement of long term residents, predatory lending and purchasing, the transfer of generational wealth, and poverty. The list goes on.

Quantitative research also reductively shoehorns processes like redlining into traditional regression models. When the null hypothesis is “no impact,” we imply that there is even a remote possibility that structural racism was not harmful, when we know that it was and still is. In this context, it’s also modeled like a discrete event that happened and ended. By recognizing the franchise model, we can clearly see that racism in housing continues to this day.

Where will they play?

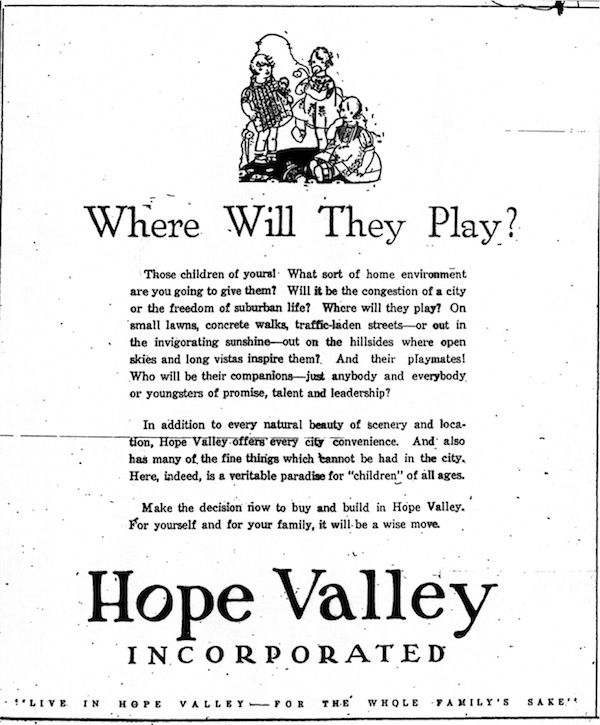

Following are two examples of what Tia Hall calls “the franchise model” of racism and housing in Durham. The first is an advertisement from the late 1920s for the Hope Valley housing development. While it says nothing directly about race, it is steeped in racialized, white supremacist, fear-based messaging.

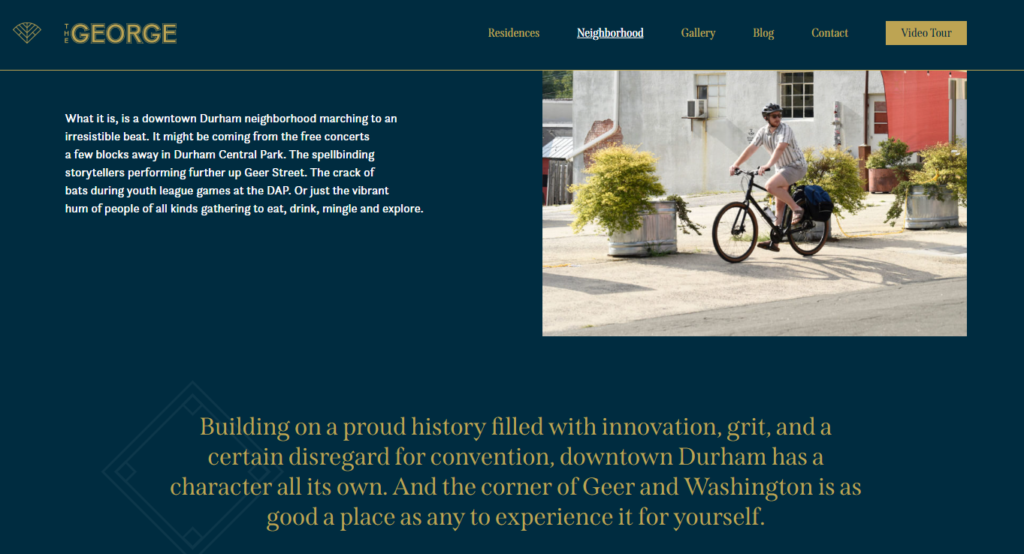

The second is the current home page for a luxury apartment complex in downtown Durham, “The George.” It pitches the neighborhood on the website as: “Past meets present in a very happy collision of authentic style and impressive substance. While the tenants may have changed, the spirit of the area lives on. Industrious, intriguing and always full of surprises.” It directly acknowledges, even celebrates displacement of previous tenants. Nearly 100 years later, “The George’s” advertisements have the same flavor of white, wealthy privilege and Black, poor exclusion.

Two all-beef patties…

In the Who Owns Durham podcast, Episode 3: Hidden Monuments of the White Franchise, Tia Hall describes the way in which both fast food franchises and racially-restrictive covenants have evolved over time.

“If you think of particular fast food restaurants, they’ve reshaped themselves over generations. Sometimes you almost don’t notice what’s happening. The same dynamic can happen when we look at what happened when we had racial covenants that were very blatant and very in your eyes. But now they have shifted; the franchise model has changed a bit so that you don’t have to talk about race, but you can be talking about ideal schooling, ideal walk spaces or greenways. It’s layered over what existed prior,” Hall explains.

“So it gives us an opportunity to look deeper and see things that we might see on an everyday basis and not consider how it’s the same franchise model.”

In order to make historical data like racial restrictive covenants and HOLC maps useful for antiracist research, we must ask different questions and design our analyses differently. Research should be more expansive and centrally highlight ways to make change. But fundamentally we should start with, ‘who asked for this?’ and ‘who benefits from this?’ At DataWorks, if the answers to these questions aren’t ‘those most impacted,’ it’s a nonstarter.

Note: This post was written by Libby McClure and L’Tanya Durante of DataWorks NC and is cross-posted on the DataWorks website.