HIH In the Classroom

With generous funding from the Civic Switchboard initiative, members of the Hacking into History (HIH) project team partnered with local educators in Durham, North Carolina in October 2021 to launch The Civic Educators Pilot project.

How can educators use primary source documentation to facilitate place-based historical learning in classrooms? Do these approaches deepen understanding, particularly with difficult subject matter? These were some of the guiding questions that motivated the Civic Educators pilot project, which ran from October 2021-August 2022.

Five educators from five Durham Public Schools (Club Boulevard, Riverside High, Southern High, Durham School of the Arts, and Jordan High School) were selected to be in the inaugural Civic Educator Fellows cohort. Each Fellow worked on developing activities and exercises for using the HIH platform and other primary source documents in their classrooms to tell the story and impact of racial covenants, race-based housing restrictions found in property deeds in Durham, North Carolina. Below we share classroom experiences from our cohort educators, who were joined by members of the HIH Project Team.

Cohort Site #1 Club Boulevard Elementary is a magnet elementary school with the mission of supporting an “intentionally diverse and inclusive community where we grow as human beings.” As part of our four-day visit, the Cohort Educator for this site began with reading The Streets are Free by Kursusa. After completing the book, the Cohort Educator guided students in a discussion of different themes from the book using Cultural Representation Reflection.

Over the next few days, the group learned some of the basic vocabulary related to our project. Terms such as “deed”, “loan”, and “segregation” were presented along with a brief example of the term as it is used. For example, segregation was described as “when people from different races are kept separate” and examples of settings where segregation took place included schools, houses, and buses.

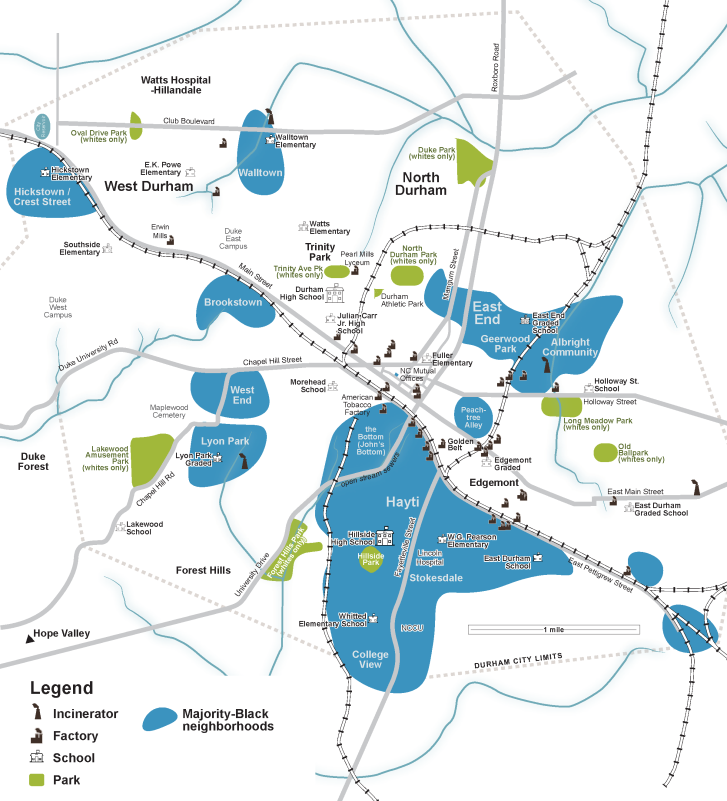

The group also did an exercise where students were divided into two groups based on arbitrary characteristics (i.e., those wearing shorts). One group was given nicer candy and able to sit in comfortable spots around the classroom (i.e., near the windows or in chairs) while the other group received less popular candy and were asked to sit on the floor. The so-called “Lollipop exercise” was originally developed to demonstrate how segregation functions in American society. Students also learned about the Hayti community in Durham, a once thriving and successful African’American community in the Jim Crow South (post Civil War-1960s) using resources adapted from the K12 Carolina Constitutional Rights Foundation lesson plan, which proposes activities dealing with the impact and after-effect of forced redevelopment under the guise of “urban renewal in Hayti. A final activity included discussing and reflecting on a map created by HIH Project Member Tim Stallmann visualizing the proximity that majority Black neighborhoods had to parks, factories, schools, and incinerators in 1937.

Students were asked to reflect on the major ideas shown in the map and to consider how proximity to these things may have impacted the people living in those communities.

Cohort Site #2 Riverside High School serves students in grades 9-12 in Durham and ranks in the top fifty most diverse schools in the state. Before the class site visit, students reviewed a vocabulary list which introduced relevant terms such as “racially restrictive covenant” and “red-lining.” These terms were meant to help prepare students for engaging with the context surrounding the historical documents in the HIH project.

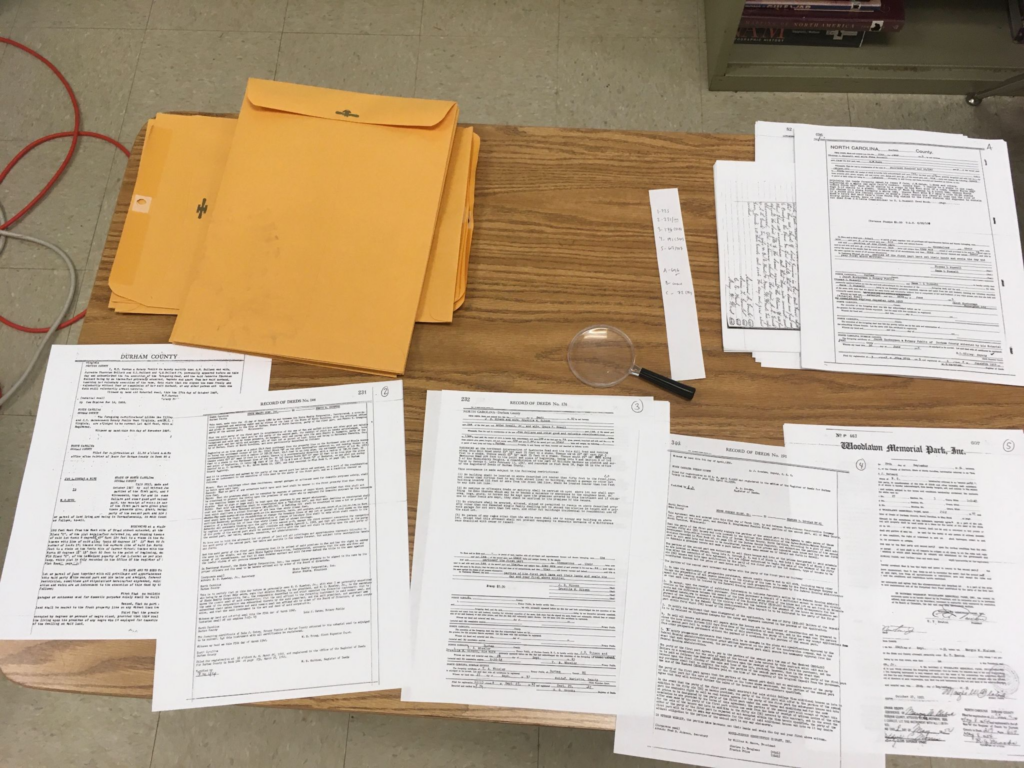

After reviewing vocabulary, the class was broken into small groups to review a packet of printed out property deeds. Each packet contained the same ten deeds; five contained racial covenant clauses and five did not.

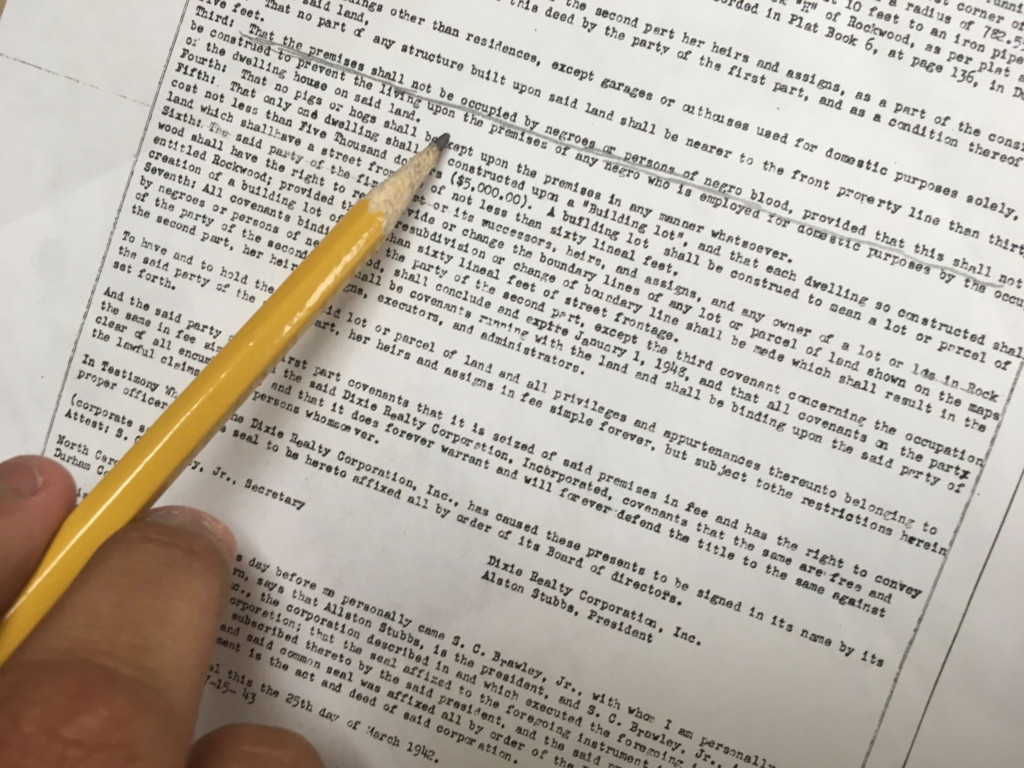

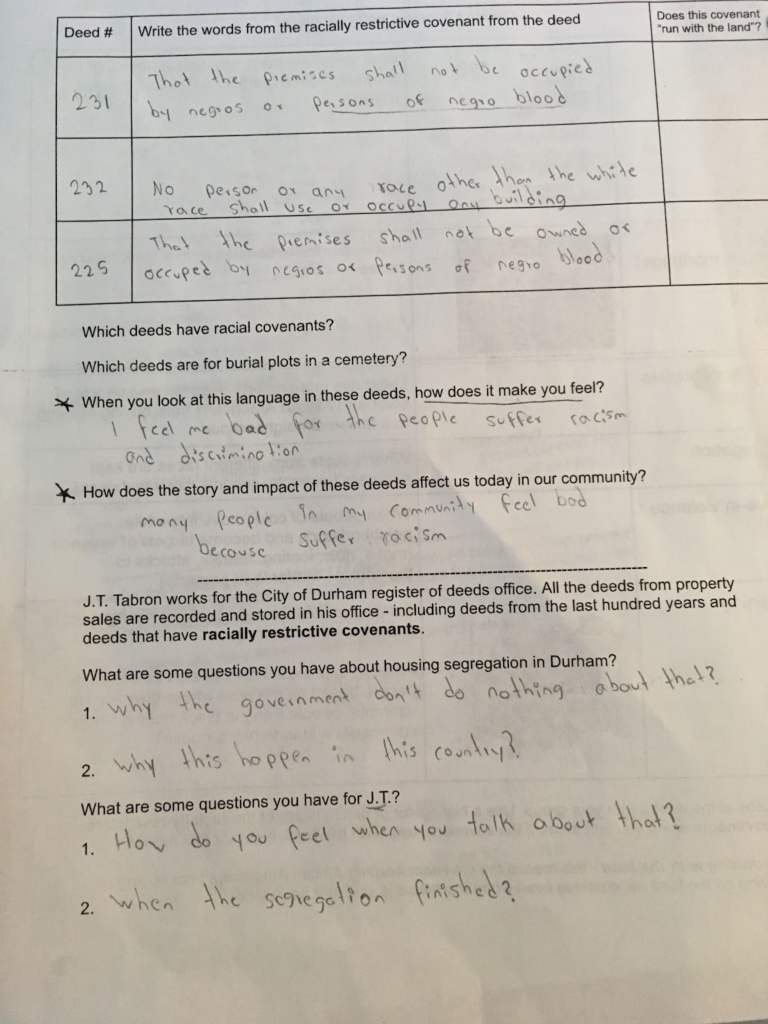

Students were instructed to review each deed in the packet and to highlight the text if and when they found a covenant containing racial clauses in them. Once they identified deeds with racial covenants in them, students wrote out the text of each clause. They were also asked to indicate where deeds had an additional clause known as “running with the land”, which stipulated that these restrictions would remain attached to the property even after transfer. After the deeds were sorted, students answered the following questions:

- Which deeds are for burial plots in a cemetery?

- When you look at this language in these deeds, how does it make you feel?

- How does the story and impact of these deeds affect us today in our community?

After the exercise, students reflected on how the covenants made them feel. In particular, they mentioned seeing locations they recognized represented in the deeds. They found the experience “powerful” but also had a hard time “believing that things like this happened in the past.”

Interested in reading more about the Civic Educators Project? Click here.

In June 2023, the Hacking into History Project will release a draft version of the Curriculum Guide, a resource for Durham educators interested in teaching about the history of racial covenants here. Stay tuned!